For the last 6 weeks, I have been making forecasts of the number of seats that each party will get in the 2017 General Election. If you have been following my forecasts, you will know that I have developed a variety of prediction models which all predict something different. With 10 days to go, I decided it was high time to settle on a single Final Model which is described in this post.

First a reminder of the 5 models I developed.

- URS – Uniform Regional Swing, now superseded by URS+S.

- URS+S – Uniform Regional Swing + Standown Adjustment

- URS+T – Uniform Regional Swing + Tactical Voting

- EU16R – Brexit Realignment

- nURS – Non-Uniform Regional Swing

For more details on the methodology of all 5 models, please read my prediction for the seat of Bath . The same process described for Bath is then repeated for all seats to arrive at my forecasts.

Until now, my official forecast was given by my URS+S model whilst my URS+T model was an alternative forecast. Both my Brexit Realignment & non-URS models were intended as a sense check for the other two models but increasingly I have hinted that these models may become more important. I have now made the decision to retire my URS+S and URS+T models, bring my EU16R and nURS models up to date and use an average of these two models as my Final Model prediction.

FINAL MODEL = Average of (revamped) Brexit Realignment Model & (revamped) non-Uniform Regional Swing Model.

Let me explain how I came to this conclusion.

Is 2017 a normal election or a realignment election?

In 2015, there was no question that Scotland saw a fundamental realignment of voter behaviour that allowed the SNP to sweep the board and become the dominant party in Scotland for the first time. The rest of Britain saw a more normal election with what amounted to a realignment among the smaller parties (Lib Dems, UKIP & Greens) but the fundamental Conservative/Labour battle largely followed traditional patterns.

Then came the EU referendum in 2016 which revealed a new fault line in British politics which had always been there but was now in the open. I estimated that 400 out of 650 seats voted Leave but what threw everything up in the air was that the likelihood of a seat voting Leave bore almost no relation with the 2015 General Election results (with the exception of the Nationalist seats which were overwhelmingly Remain seats). The tables to the left show that outside of London (EngXL), 75% of Labour & Conservative seats voted Leave.

but what threw everything up in the air was that the likelihood of a seat voting Leave bore almost no relation with the 2015 General Election results (with the exception of the Nationalist seats which were overwhelmingly Remain seats). The tables to the left show that outside of London (EngXL), 75% of Labour & Conservative seats voted Leave.

My favourite chart which shows how the referendum appeared to change the rules is the one below. This is for the 573 seats of England & Wales and the seats have sorted into deciles based on a demographic variable which is the % of households in each constituency that do not own a car. The reason for choosing this variable is that my analysis showed it was the greatest differentiator between the Conservatives & Labour in 2015. You can see in the lowest decile on the left (where on average only 12% of households do not own a car), the Conservatives had a 43% lead over Labour. Conversely in the highest decile on the right (where on average 51% of households do not own a car), Labour had a 33% lead over the Conservatives. The effect of these extreme differences is that in the lowest deciles, the Conservatives took all seats whilst Labour took practically all the seats in the highest deciles.

When you stop and think about it, the NoCar Household rate makes a lot of sense. After all, what kind of households are least likely to own a car? The answer is the young, the poor and those living in city centres. All are demographics known to vote Labour and the opposite demographics elderly, rich, rural dwellers are known to vote Tory. For the smaller parties, the relationship is less strong though the Lib Dems are closest to the Conservatives whilst the Greens do best and UKIP do worst in areas with few car owning households.

The black dashed line in the left hand chart is the Leave vote share for each decile. I still find it astonishing that there is no relationship with the NoCarHousehold rate until you get into the highest decile which is the only decile that voted Remain on average. So the strongest differentiator of voting intentions in 2015 turned out to be almost useless in 2016.

Instead, the referendum vote was driven by Class, Education and Occupation. The chart below is for something I call the Occupational Differential (for England & Wales again) which is the %people working in Managerial/Professional roles minus the % people working in Lower Routine roles. A positive differential indicates that managers/professionals outnumber routine workers, a negative differential indicates that routine workers outnumber managers/professionals. Occupation is a good proxy for Class which is why I like this variable.

This time the relationship between Occupation and Leavers is strong. It is also strong with areas with high numbers of UKIP and Labour voters.

So to come back to the question of whether the 2017 election is going to be a normal one or a voter realignment, looking at voter intention from the polls in terms of Class and Referendum voting will give us a clue. Charts B4 & B5 below will be familiar to you if you have been following my Opinion Poll Tracker.

B4 shows that among Remain voters, Labour has gained over 10% since the election was called and are approaching 50% of all Remain voters. B5 shows that the Conservatives are up almost 10% among Leave voters and were approaching 2/3 of all Leave voters though they have slipped back a bit recently. So Remainers are becoming more Labour whilst Leavers are becoming more Tory. But my earlier chart for the Occupational differential shows that in middle class areas, the Conservatives were ahead of Labour and those areas tended to vote Remain whilst in working class areas which tended to vote Leave, Labour was ahead of the Conservatives.

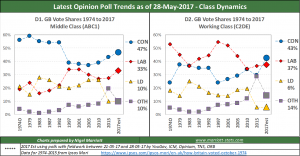

The next chart is a new one for my Opinion Poll tracker and for me is the most striking of all that I have seen in 2017. D1 & D2 show voting intention by class in 2017, based on pollsters that segment their respondents using the standard ABC1 (middle class) and C2DE (working class) definitions, and how this compares with all elections since 1974. The earlier data for 1974-2015 comes from Ipsos-Mori who have carried out post election polls over that timeframe to identify voting patterns by demographics.

For the first time ever in British political history, the Conservatives are expected to be the largest party among the working class whilst Labour could achieve their highest ever vote share among the middle class. It is well known that prior to 1974, class based voting was even stronger than shown in the charts here so 2017 could be the election where Labour which founded to represent the interests of the working class find themselves supplanted in that role by the Conservatives. In effect, if you consider charts D1 & D2 together, class ceases to be differentiator between the two main parties. If that is not a sign that 2017 is a realignment election then I don’t what is.

Which of my models is the best in a Realignment Election?

Until now, I have used my URS+S (Uniform Regional Swing + Party Stand Down Adjustment) model as my official forecast with a Tactical Voting variant of this as an alternative forecast. At the heart of this model is the assumption that whilst swings between the parties vary between the regions, within each region a similar swing can be expected across all seats in the region. This was certainly the case in Scotland in 2015 when it behaved differently to the rest of the UK but within Scotland, a largely similar swing from Labour & Lib Dems to the SNP was observed. But in a realignment election, I do not think it is tenable any longer to assert that a uniform swing will be observed within each region. Instead the swing will be dependent on the Referendum vote and the Class make up within each seat. Accordingly, I am retiring my URS+S and URS+T models. It is still possible that these models will be accurate at the national level but given that there are significantly more Leave than Remain seats, I would surprised if this was the case.

This leaves me with my EU16R (Brexit Realignment) & my nURS (non-Uniform Regional Swing) models. Unlike 2015, very few constituency level polls have been published in this election. Only 5 have been published but I have used these to see which of my 4 models were closest to the seat polls. In all 5, my URS+S & URS+T were not close and it was either my Brexit Realignment model or my non-Uniform Regional Models that were closest. The split was as follows:

- EU16R best fit to seat poll – Kensington, Battersea, Brighton Pavilion.

- nURS best fit to seat poll – Bath, Edinburgh South

Frustratingly, all 5 seats are strong Remain seats and I would dearly love to have some polls in strong Leave seats. The nearest I have been able to get to this has been the sub-regional splits shown within the Welsh Barometer Polls which I first explored in my forecast of Cardiff South and Penarth.

What I find interesting is that my two models are very different in how they work, yet they are both capable of forecasting seats to some degree. This observation is one reason why I gravitated towards to taking an average of both models as my Final Model. Before I could do this, I needed to revamp both models and I will explain what changes I made and in doing so, give a reminder of how they work.

My Revamped Brexit Alignment Model

Unlike my other models, my EU16R model is not directly linked to the latest polls. Instead it uses a Brexit Voter Segmentation approach I developed last year using Lord Ashcroft’s “Exit Poll” which I used first to predict by-elections (including Richmond Park & Copeland). The model splits the 2015 voters for each party into 5 segments (3 Remain & 2

Leave as shown in the graphic) and I am still happy with this basic segmentation. One reason is that research by YouGov has identified that the nation is now split 68:22 when it comes to Brexit, not 52:48, after they identified what they called the ReLeaver voter i.e. someone who voted Remain but who accepts that Britain is now leaving the EU and does not want a second referendum. The ReLeaver segment is a very good fit for my Economic Risk Remainer segment which I identified last year as someone who had no love of the EU but was worried about economic risks if Britain left the EU.

My original version of this model made rather crude assumptions about how people would vote if a realignment took place. For example, I assumed that 100% of Lib Dem Brexiteers would defect to the Conservatives and 100% of Conservative Pro-EU Remainers would defect to the Lib Dems. This worked well enough to make the model a good sense check but increasingly I have been using voter switching information which I show in charts S1, S2 & S3 of my Opinion Poll Tracker to identify more accurate realignments. For example, this data now suggests that the Conservatives are now only picking up 50% of Lib Dem Brexiteers but in addition they are picking up 20% of Lib Dem Econ Risk Remainers (or ReLeavers). For Conservative Pro-EU Remainers, the data suggests that all have defected from the Conservatives but they have split 60/40 between Labour & the Lib Dems.

I have made a variety of more refined realignments which are all broadly consistent with the Switching data (charts S1, S2 & S3) and the Brexit data (charts B1 to B5). In addition, ICM are the only pollster who attempt to split between Leavers & Remainers within each of the main parties and I have used this information as well to refine my model. The reason why I think you need to link both Brexit & Switching data rather than just using Switching data alone is because of my contention that we are in a Realignment election and therefore the probability of a voter switching depends on how they voted in both 2015 & 2016 if indeed they did vote (which is a separate question about likelihood of turnout!).

My final refinement was to add the Party Stand Down Adjustment model to my Brexit Realignment Model. This was first explained in my North Norfolk prediction and my current version assumes that residual UKIP voters will split 2:1 between the Conservatives & Labour in seats where UKIP have stood down.

My Revamped non-Uniform Regional Swing Model

The main refinement to my nURS model has been to add in a Party Stand Down Adjustment effect (same as the one described above for EU16R) but I have also reduced the sensitivity of the model to the Leave vote following the publication of a seat poll for Battersea. The nURS model works by first taking my URS forecast and then adjusting the Conservative vote depending on whether the Leave vote was above or below the regional average. For example, if the leave vote in a seat is 10% above the regional leave vote, then I used to increase the Conservative vote by 10% which was an CON:LEAVE ELASTICITY of 1.0. However, the latest seat polls are now suggesting that the elasticity is +0.7 instead. This means in a seat where the Leave is 10% above the regional leave vote, the Conservative vote will be 7% higher than under URS.

The second adjustment has been to how I adjust the other parties if the Conservative vote changes. I have decided to keep elements of my now-retired URS + Tactical voting model. In that model, 67% of the available tactical votes would be allocated to the party best placed to beat the Conservatives. What I have done for my nURS model is that in seats where the Conservative vote is reduced due to the Leave vote being below the regional Leave vote, then 60% of the reduction is added to the party best placed to beat the Conservatives and 40% is allocated to the next best placed party. I have reduced the figure to 60% from 67% for two reasons. First the few seat polls that have occurred show that the dreams of the “progressive alliance” voting tactically does not appear to be working that well. Second, I am convinced that part of the improvement in the Labour vote in recent weeks is because of tactical voting intentions and so the URS model will already have taken this into account.

Why I decided to average my EU16R & nURS predictions for each seat

I have already hinted at one reason earlier when I remarked that the 5 seat polls that I am aware of are evenly split between the two models in terms of best fit. The second reason occurred when I ran the latest forecasts for all 4 models as shown in chart P0.  If you look at my URS+S and URS+T models, this suggested that tactical voting could prevent 26 Conservative gains. At first my revamped EU16R and nURS models suggested that nURS (which now incorporates a form of tactical voting) would prevent 11 gains. But this obscured the fact that the two models gave quite different results for Scotland & Wales. EU16R said the Conservatives would do well in Wales and poorly in Scotland whilst nURS said the reverse including taking 10 seats of the SNP in Scotland. In England the two models gave quite similar forecasts.

If you look at my URS+S and URS+T models, this suggested that tactical voting could prevent 26 Conservative gains. At first my revamped EU16R and nURS models suggested that nURS (which now incorporates a form of tactical voting) would prevent 11 gains. But this obscured the fact that the two models gave quite different results for Scotland & Wales. EU16R said the Conservatives would do well in Wales and poorly in Scotland whilst nURS said the reverse including taking 10 seats of the SNP in Scotland. In England the two models gave quite similar forecasts.

My interpretation of these discrepancies was that it was difficult for both models to account for the Nationalist vote and I was unclear as to which approach was better. I decided that taking an average of the two models would resolve this difficulty and this was enough to make up my mind that this would be my Final Model as shown by the PRED column in table P0.

From now on, my general election prediction for 2017 will be based solely on this Final Model. However, I will continue to record the predictions of each of the 4 models in the spreadsheet that I provide along with my forecast so that you can see how different or not the forecasts are.